BKLNER: Who’s Falling Behind On Taxes In Brooklyn?

By Bill Richling

February 25, 2021

Hotels, parking garages, condos, walk-up apartment buildings – everywhere you look, Brooklyn property owners are behind on paying their property taxes, way above the city average, with no relief in sight.

A new analysis from City Comptroller Scott Stringer’s office finds that, as of February, $1.3 billion in real estate tax payments, the city’s largest single revenue source, were overdue. That’s about 4.5% of the total $29.6 billion in property taxes the city expected to collect in Fiscal Year 2021.

Even if, as the comptroller’s office expects, that number drops to 3% by the end of FY2021 as late payments come in, the proportion would still be significantly higher than the FY2020 figure of 1.8% and even the previous post-Great Recession peak of 2.17% in FY2011.

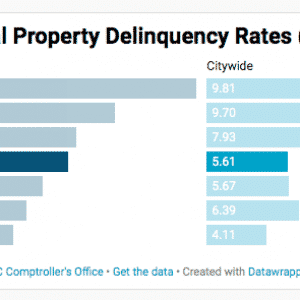

Hotels

Unsurprisingly, given the pandemic’s devastating impact on tourism, hotels had among the highest delinquency rates of any property type: citywide, nearly 10% of hotel property tax has gone unpaid. But in Brooklyn, that number is nearly double: 17.8%. In other words, nearly one of every five tax dollars due from Brooklyn hotels is unpaid.

Just last week, the boutique Williamsburg Hotel became the latest Brooklyn hospitality business to file for bankruptcy. Tillary Hotel in Downtown Brooklyn, and WB Bridge Hotel that was under development in Williamsburg filed for bankruptcy in late December.

“The reason for Brooklyn’s higher delinquency rate is that many of the hotels in Brooklyn are owned by single asset entities, usually by relatively small business houses and owners, who have run out of resources,” Vijay Dandapani, President & CEO of the Hotel Association of New York City.

Dandapani said the Association was pushing the city to lower or temporarily eliminate the punitive 18% penalty interest rate normally imposed on unpaid tax bills. The Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) has also pushed for the policy change, though thus far, Mayor Bill de Blasio remains opposed to it.

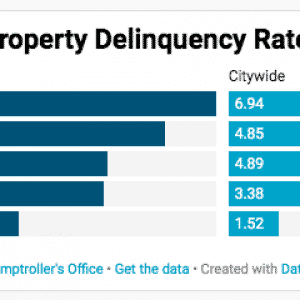

Garages and Gas Stations

Despite a widely-discussed surge in car ownership during the pandemic, garages and gas stations also had a high tax delinquency rates: 12.2% in Brooklyn and 9.7% citywide.

Transportation planner Charles Komanoff cited data that suggests the increase in new car owners has been overblown, and said it was likely overall vehicle travel had decreased, cutting into garage and gas station profits.

“Sure driving’s mode share is almost certainly up, but the denominator shrank even more,” Komanoff told Bklyner in an email. “This would contra-indicate increased driving that would cause more fill-‘er-up.”

What’s more, some parking garages owners told the Wall Street Journal in August that they had lost thousands of customers as car-driving residents, who tend to have higher incomes, packed up and left the city during the pandemic.

Retail

Retail buildings are also faring worse in Brooklyn, with 7.1% in unpaid taxes, compared to 5.7% citywide. In fact, Brooklyn had a higher rate of unpaid property taxes across nearly every major property category, from condos to factories to garages and gas stations.

Eli Dvorkin, Editorial & Policy Director at the think tank Center for an Urban Future, suggested the prevalence of immigrant- and minority-owned small businesses in the borough might be part of the explanation.

“Many lacked the cash to survive weeks of lockdown and others have struggled to access government relief programs, even as revenues have plunged by 50% or more,” Dvorkin said. “Higher rates of tax delinquency among Brooklyn’s commercial landlords—especially for storefront businesses—indicates just how difficult it’s been for their tenants to keep up with the rent and other expenses.”

Citywide, the delinquent amount for commercial properties totaled $740 million, or just over half of the overall delinquent amount.

Housing

On the residential side, discrepancies between Brooklyn and the citywide numbers were similar.

Condominiums had higher delinquency rates than rental apartments or coops, the comptroller’s report said, because single-owner units are more likely to fall behind than multi-tenant buildings. But condos make up a relatively small share of the city’s total housing stock; about 67.3% of the city’s households rent their home.

Stringer, who is running for mayor, has called on the state to cancel rent for those affected by the pandemic, and previously called for $2.2 billion in state spending to help renters as well as small mom-and-pop landlords.

A statewide emergency relief program for residential tenants introduced last year distributed less than $40 million of the slated $100 million because too few people met the program’s strict eligibility requirements.

While Manhattan’s 4.1% delinquency rate was lower than that of the outer boroughs, the total amount owed from properties in that borough was higher than the rest of the city, because Manhattan accounts for about 63% of all property taxes due. Manhattan properties owe about $771 million in unpaid taxes, while other four boroughs combined owe about $570 million.

Ana Champeny, Director of City Studies at the nonprofit Citizens Budget Commission, called the increased delinquency rate “concerning” but said it did not pose an immediate risk to the city’s fiscal health, because the de Blasio administration had factored it into its FY21 budget calculations.

“Fortunately, because the City budget accounted for a higher rate of delinquency than usual in this year and next,” Champeny said, “the level of non-payment projected by the Comptroller should not create a major revenue shortfall.”